Early Years and Exile

Jean Blaise LeJeune was born approximately April 22, 1750, in Pisiguit (now Annapolis Royal), Acadie (present-day New Brunswick, Canada). His parents were Jean Baptiste LeJeune and Marguerite Trahan. Blaise’s childhood was marked by the tumultuous events of the Acadian expulsion (Delaney, 2005).

He was listed in a census in Port Royal, Nova Scotia in 1752, and listed as two years old, his brother Jean-Baptiste age three, and his sister Marguerite at two months old. In 1755, British forces forcibly exiled his family and many other Acadians from their homeland, along with other Acadians. Blaise, who was just a child at the time, found himself uprooted and transported to Maryland. By 1763, the war had ended, and he was considered an orphan among the Acadians being freed in Port Tobacco, Maryland. This was recorded in a 1763 census in Port Tobacco, Maryland.

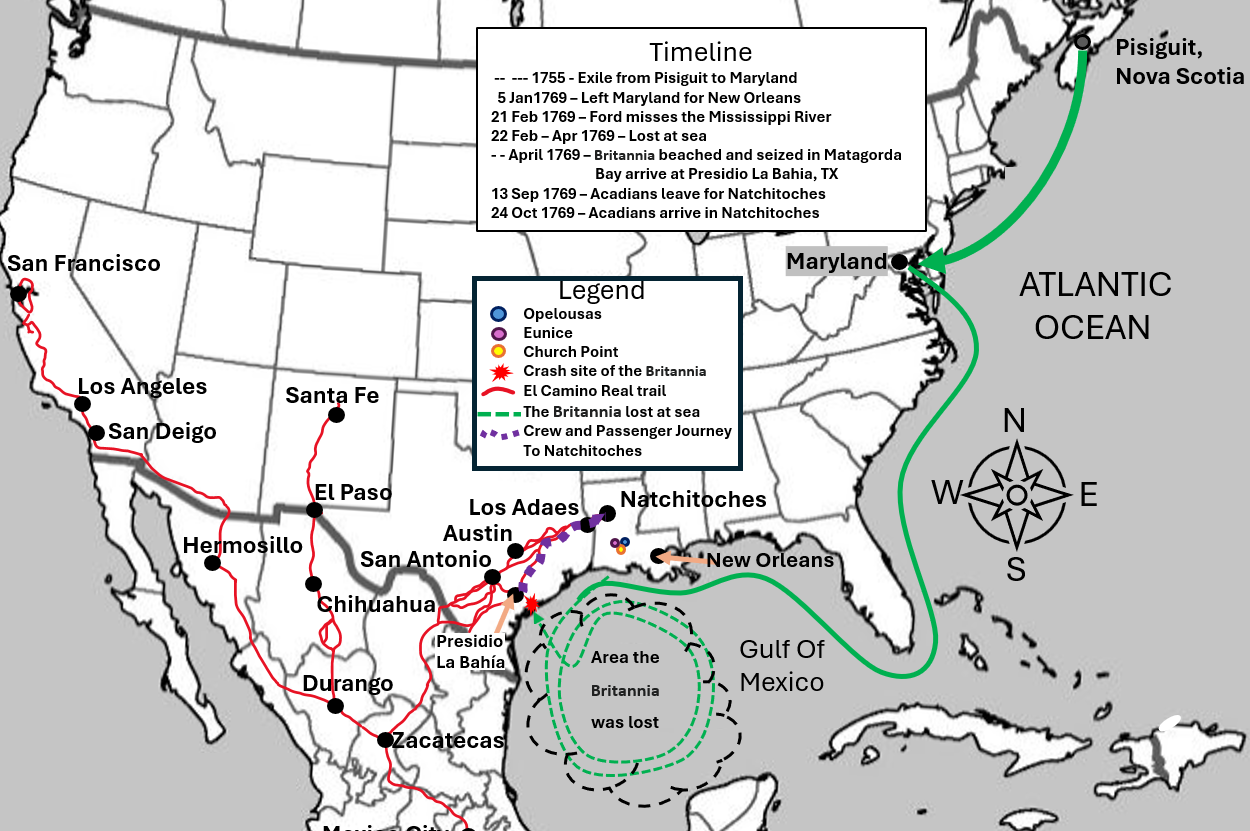

Figure 1. Migration of Jean Blaise LeJeune and his family

The Journey to Louisiana

Blaise embarked on a remarkable journey. After the Seven Years War, he, his siblings, Uncle Honore Trahan, and other family members, left Maryland for New Orleans, Louisiana. Thirty-two Acadians chartered the ill-equipped English schooner The Britannia. Captain Philip Ford misrepresented the condition of the ship and its provisions. Ford used the Germans and Acadians aboard to make the necessary repairs to the ship, and they began their voyage to New Orleans, LA, on January 5, 1769. Blaise was eighteen years old (Wood, Acadians in Maryland, 1995).

Ford’s navigation maps were inaccurate. After arriving in the Gulf of Mexico, Captain Ford missed the mouth of the Mississippi River disregarding the counsel of the crew and passengers. It was clear that the captain was incompetent and ill equipped to navigate to their destination. He refused the requests of the passengers to turn around and became lost after a strong storm. They remained lost in the Gulf of Mexico for some time and provisions became scarce. The crew and passengers cooked and ate anything that was considered edible. Captain Ford recalls that “rats, cats, and even all the shoes and leather in the vessel” were used for food (Brasseaux, 1984). The passengers convinced the captain to turn around by threatening mutiny.

Eventually The Britannia was beached in Matagorda Bay, Texas, and the survivors were saved by don Francisco Tova, a Spanish commander of Presidio La Bahía. They were brought to Presidio La Bahía where they were detained. On September 13, 1769, they set off to Natchitoches via the El Camino Real Trail, where Captain Ford and his crew faced charges that were levied against them by the passengers.

Blaise and his family arrived in Natchitoches on October 24, 1769. Alejandro O’Reilly, governor of Louisiana, made provisions for the Acadians in Natchitoches, including land. O’Reilly said, “The English families have returned to Pensacola (Brasseaux, 1984). I have given the Germans and Acadians lands, tools for their fields, and two hundred and sixty-seven pesos fuertes in money. The settlement of these poor families is very costly to the exchequer.” (Wood, Acadians in Maryland, 1995) But the Acadians were focused on rejoining their kin in Southern Louisiana, so Blaise and his family settled for a short time in Iberville, LA.

Figure 2 – Photo of Presidio La Bahía in 1800’s

Figure 3 – Modern day Presidio La Bahía, TX

Marriage and Family

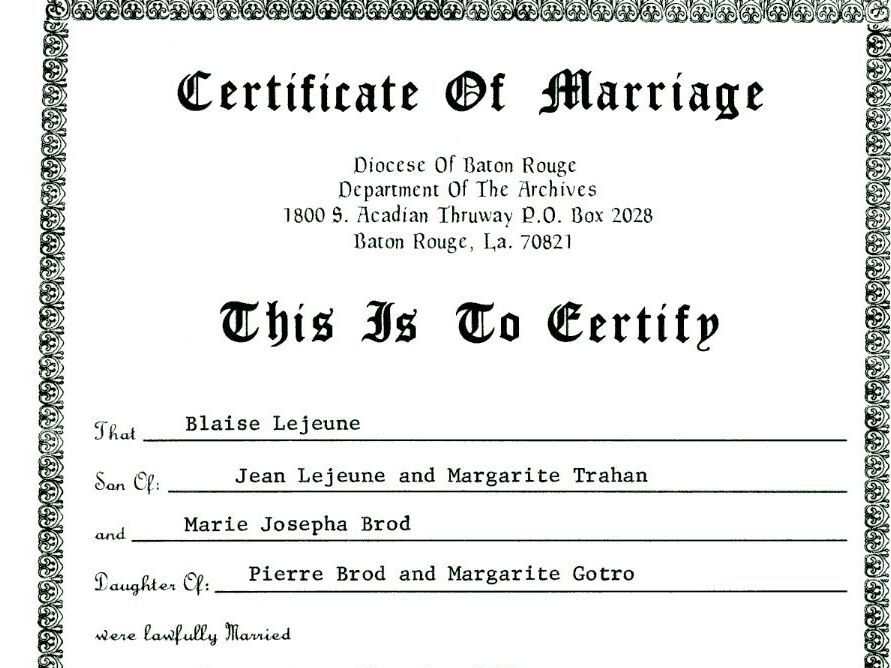

Blaise married Marie Josèphe Breaux on November 3, 1773, at Ascension Church (now Donaldsonville) (Department of the Archives, 1800 S. Acadian Thruway, Baton Rouge, La. 70821 – Vol 1 Pg 125). Their union would shape the course of their family’s history. Blaise and Marie Josèphe became parents to seven sons and two daughters, leaving a lasting legacy in Louisiana (genealogy.com, n.d.). His Children are listed below:

Jean Blaise LeJeune Jr. 1774–1848

Joseph LeJeune 1776–1818

Jean Baptiste LeJeune I 1777–1837

Joseph Ozier LeJeune 1780–1825

Hilaire LeJeune 1782–1786

Marie Celeste LeJeune 1783–1816

Marie Angelique LeJeune 1786–1854

Figure 4 – Blaise’s Marriage Certificate (reproduced from church records)

Blaise LeJeune and his family settled in the Faquetaique Prairie near Eunice and Church Point, Louisiana. His brother Joseph anglicized and changed his surname to Young. Jean-Baptiste moved to Avoyells Parish. Blaise obtained land on both the upper Bayou Plaquemine Brulee (southwest of Opelousas Post) and in the Faquetaique Prairie (near Eunice). This area became a center for the largest line of LeJeune descendants. Blaise was a farmer by trade and worked at a homestead there.

Bayou Blaise LeJeune is named after him, and to this day can be found at 30°23’16.2″N 92°17’53.5″W. It is listed on some maps as Blaise LeJeune Gully to include Google Maps™. Census records from 1774 and 1777 captured glimpses of his life alongside his wife and children. Also, some genealogists credit Jean Blaise LeJeune with founding Youngsville, LA. This is a contradiction to the cities’ recorded history and is highly debated among researchers.

Military Service During the American Revolution

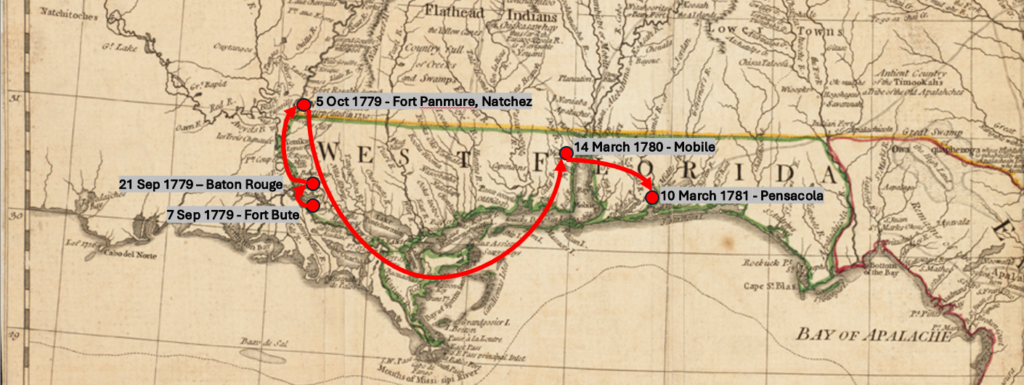

Blaise LeJeune’s impact extended beyond family life. He served in the Opelousas militia as a fusilier, contributing to the defense and development of the region (Daughters of The American Revolution, n.d.). In 1779, the Spanish declared war on England joining the Americans in hostilities with the British. The Opelousas militia marched with General Bernardo de Galvez, the General-Governor of Louisiana, in the battle to take Fort Bute on September 7, on Bayou Manchac. September 12-21, General Galvez would lead the same men in the siege of Baton Rouge where they repealed the British occupation. They later captured Fort Panmure in Natchez on October 5.

Figure 5 – The battles of General Galvez during the American Revolution

The fight against the British caused many in Blaise’s militia to continue to serve under General Galvez and sail to West Florida, where they captured Mobile on March 14, 1780. They would go on to defeat the British in the Siege of Pensacola from March 9 – March 10, 1781 (Frasier, 2022). By capturing Pensacola, the Spanish forces under General Bernardo de Galvez effectively cut off British supply lines and weakened their strategic position in the southern colonies. This, combined with other factors, contributed to the British defeat at Yorktown in October 1781, aiding in the success of the American Revolution (https://www.battlefields.org/, n.d.).

Legacy and Final Resting Place

During the late 1700s on through 1900s, yellow fever was ravaging the area. Louisiana experienced hundreds of outbreaks that killed thousands of settlers. The second largest epidemic in Louisiana took place from 1811 to 1817 and spread as far north as Natchez (Kelley, 2011). It is during this epidemic that Jean Blaise LeJeune passed away in the year 1812, in Opelousas, St. Landry Parish, Louisiana. Blaise left behind a legacy intertwined with the history of St. Landry, Acadia, and Evangeline parishes.

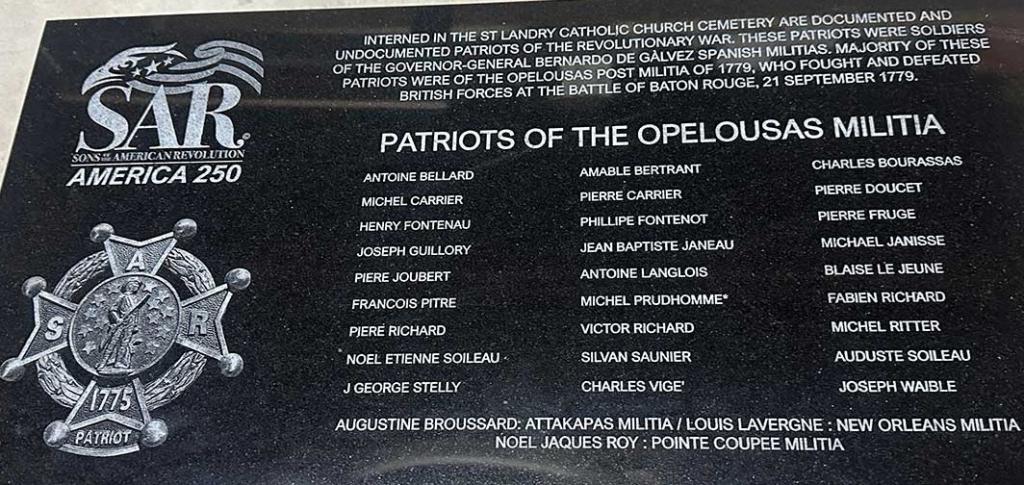

The area in and around Opelousas had two mass graves where they were burying those who died of yellow fever. One in Opelousas and one in Washington just north of Opelousas. To this day, the cemetery in Washington is named the yellow fever cemetery. Mass graves were necessary due to the large number of people dying from yellow fever. It is assumed that Blaise contracted yellow fever because his name is found in the records for these mass graves in the Saint Landry Church Cemetery in Opelousas, LA. Today, his exact resting place is unmarked and unknown, but the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution (NSSAR) have placed a marker for Blaise and other patriots who met the same fate. His name is etched in white against a black marble marker just inside the entrance of the cemetery. A memorial with the NSSAR crest and logo etched into it. The inscription on the memorial says:

“Interned in the St. Landry Catholic Church Cemetery are documented and undocumented patriots of the revolutionary war. These patriots were soldiers of the Governor-General Bernardo De Galvez Spanish militias. Majority of these Patriots were of the Opelousas Post Militia of 1779, who fought and defeated British forces at the battle of Baton Rouge, 21 September 1779.”

Figure 6 – NSSAR Memorial for patriots of the American Revolution including Blaise LeJeune

Remembering Blaise LeJeune

Jean Blaise LeJeune’s story is a testament to the enduring strength and spirit of the Acadian people. His life, marked by hardship, resilience, and unwavering dedication, leaves an indelible legacy that continues to inspire future generations. Orphaned at an early age and exiled from his home, he undertook a perilous journey to join his kin in settling the Louisiana frontier.

Blaise’s significant contributions in the American Revolution and the establishment of his family in Louisiana is a profound narrative of perseverance and triumph. His name, etched in history and commemorated in memorials, reminds us of the enduring impact one individual can have on their community and beyond. Through his life and legacy, Jean Blaise LeJeune exemplified the true spirit of courage, commitment, and enduring heritage.

Bibliography

Brasseaux, C. A. (1984). The Britain Incident, 1769-1770: Anglo-Hispanic Tensions in the Western Gulf. The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, 87(4), pp. 357-370 . Retrieved August 19, 2024, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/30236968

Committee, W. o., & Jane G. Bulliard, C. e. (2015). The Wall of Names at the Acadian Memorial. Opelousas, LA: Bodemuller.

Damon Veach, G. D. (n.d.). Jean Blaise LeJeune I. Retrieved from https://www.findagrave.com/: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/142079937/jean-blaise-lejeune

Daughters of The American Revolution, V. (n.d.). LEJEUNE, BLAISE. Retrieved from https://services.dar.org/public/dar_research/: https://services.dar.org/public/dar_research/search_adb/default.cfm?action=full&p_id=A069435

Delaney, P. (2005). The Chronology of the Deprtations and Migrations of the Acadians 1755-1816. Les Cahiers of the Société Historique Acadienne. Retrieved August 14, 2024

DeVille, W. (1774). Census: 8 Nov 1774 Opelousas, St. Landry, Louisiana. Mississippi Valley Mélange, vol. 1, 39. Baton Rouge, LA: Provincial Press, Claitor’s Publishing Division.

Fournerat, L. M. (n.d.). Blaise Jean LeJeune. Retrieved from https://www.geni.com: https://www.geni.com/people/Blaise-LeJeune/6000000007473328205

Frasier, A. (2022). Gulf Coast Campaign: The Forgotten Theater of the American Revolution. TheCollector.com. Retrieved from https://www.thecollector.com/gulf-coast-campain-american-revolution/

genealogy.com. (n.d.). Genealogy Report: LeJeune side of the family – Generation No. 6. Retrieved from https://www.genealogy.com: https://www.genealogy.com/ftm/v/r/o/Donna-Vroman-MI/GENE30-0006.html

https://www.battlefields.org/. (n.d.). Bernardo de Galvez. Retrieved from https://www.battlefields.org/: https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/bernardo-de-galvez

Jehn, J. (1977). Acadian Exiles in the ColoniesCensus: 7 Jul 1763 Port Tobacco, Charles, MD. Covington: KY.

Jehn, J. (2004, OCT). Acadian Genealogy Exchange. Acadian Genealogy Exchange, ed. vol. XXXIII, no. 2, 83.

Kelley, L. D. (2011, January 16). Yellow Fever in Louisiana. 64parishes.org. Retrieved August 14, 2024, from https://64parishes.org/entry/yellow-fever-in-louisiana

Revolution, N. S. (2003). Opelousas Militia Military Service, 1776-1777, Opelousas, St.Landry, Louisiana. Baltimore, MD, USA: Gateway Press.

Robillard, M. L. (n.d.). Conk/Robillard Family Tree » Blaise Lejeune (1750-1812). Retrieved August 14, 2024, from https://www.genealogieonline.nl: https://www.genealogieonline.nl/en/conk-robillard-family-tree/P32884.php

Rouge, D. o. (1980). Diocese of Baton Rouge Catholic Church Records, vol. 2, 1770-1803. Diocese of Baton Rouge Catholic Church Records, vol. 2 1770-1803, 154, 494. BatonRouge, LA.

thecajuns.com. (n.d.). Arrival of the Acadians in Louisiana. Retrieved from thecajuns.com: thecajuns.com/acadians.htm

Unknown. (1998, July 26). LeJeune Family Emigrate fom Poitou Region. Abbeville Meridional, p. 20. Retrieved August 12, 2024, from https://www.newspapers.com/image/447591682/

Veach, D. (n.d.). Genealogy Column, “Lejeunes immigrated via interesting path”. New Orleans Times-Picayune.

Ville, W. D. (2010). Census: May 1777 Opelousas, St. Landry, Louisiana. Southwest Louisiana Families in 1777: Census Records of Attakapas andOpelousas Posts, 27. Baton Rouge, LA: Claitor’s Publishing.

Wiese, J. (2024, January 5). Battle of Baton Rouge (1779). Retrieved from https://64parishes.org/: https://64parishes.org/entry/battle-of-baton-rouge-1779

Wikitree, V. (n.d.). Blaise Jean Lejeune. Retrieved from https://www.wikitree.com/: https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Lejeune-46

Wood, G. A. (1955). A Guide to the Acadians in Maryland in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. Baltimore: MD.

Wood, G. A. (1995). Acadians in Maryland. In G. A. Wood, Acadians in Maryland (pp. 35-36). LA: Gateway Press. Retrieved from www.familysearch.org/: https:/https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/memories/L891-1PQ/

Young, J. A. (1991). The Lejeunes of Acadia and the Youngs of southwest Louisiana: a genealogical study of the Lejeunes of Acadia and the descendants of Joseph Lejeune/Young and Patsy Perrine Hay.